2014 Fantasy Baseball — Missing: Jason Heyward’s Power Stroke

If you’re like me, you spend way too much time on Fangraphs. Chances are – you’re on a fantasy site after all – you’re very similar to me. Well, Fangraphs just got even better by adding heat-maps. Yes, I know, heat-maps have been available on other sites for a while – I’ve used the ones generated by Brooks Baseball frequently here at The Fix. Fangraphs’ addition, however, peaked my interest, so I decided to play around with them a bit.

Like many, I thought this year would be the year. You know, the year Jason Heyward’s abilities – raw power, patience, baserunning, and opposite field slashing doubles swing – came together for a full season. So far, it hasn’t been that way.

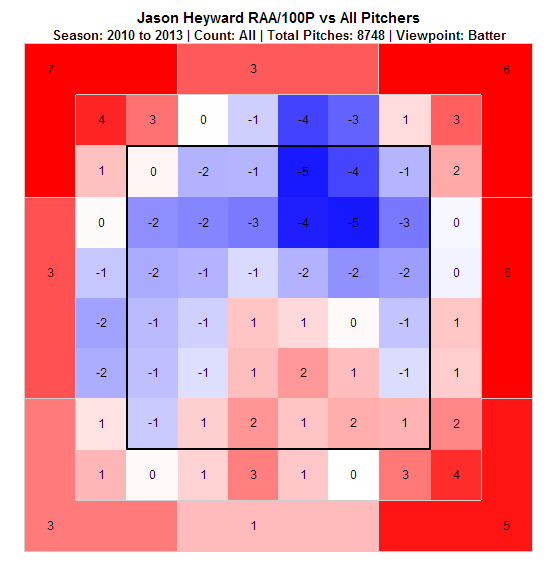

Let’s dig in. We’ll use a few different kinds of maps today. We’ll look at his contact% in a couple and his RAA/100 – runs above average per 100 pitches; Dave Cameron has a nice run down of it here – in a few. If you’re confused about RAA, don’t be. Think wOBA, kind of. Take it away Dave:

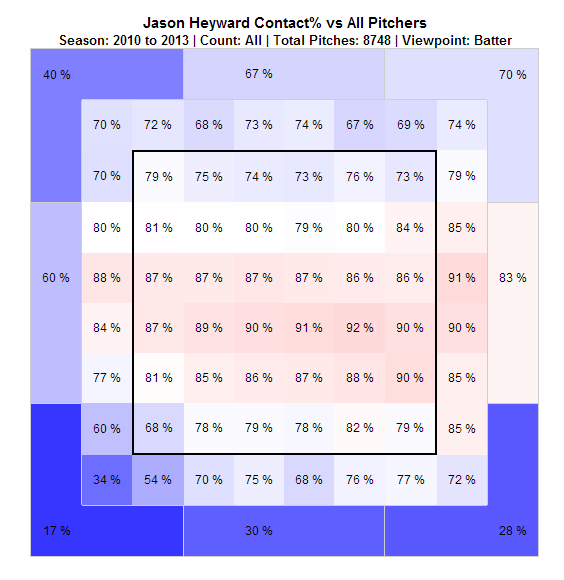

Of course, a lower contact rate isn’t necessarily worse, depending on what kind of contact a hitter makes when he does hit the ball. In reality, what you really want to look at is total production in a location, taking into account both the negative outcomes like swinging strikes and the positive outcomes on balls in play.

And that’s why I love one of our new heat maps in particular. You’ll find it labeled as “RAA/100P”, which stands for Runs Above Average per 100 pitches, but essentially, it’s a linear weights metric that gives you the sum of a batters outcomes in a specific zone.

If a batter never swings at a pitch out of the zone, he may be hitting .000/.000/.000 on pitches in that area, but it’s still a very high reward location for him because of the large numbers of called balls, which generate value for the hitter. By adding up the values of not just the balls in play, or even just the swings, but of all pitches in that specific area, we can see where each hitter (or pitcher) is generating most of their value.

In short, any number over “0” is above average. The higher the number, the better the results have been in the zone; the opposite applies for lower numbers.

Heyward’s 2014 has been eerily similar to his 2013. Last April, Heyward slashed .121/.261/.259 in 16 games. After having an emergency appendectomy, Heyward appeared in 15 games in May, slashing .178/.327/.222. It seemed like everything was lost. His patience was still intact, but his power stroke was basically gone – the appendectomy surely didn’t help. No matter, because from June 1 until the end of the season Heyward slashed .294/.373/.495 buoyed by 12 home runs. He didn’t run much, but he scored a ton of runs and even drove in a good amount, despite being in the leadoff spot.

Let’s bounce on over to 2014. Heyward’s line currently sits at .240/.332/.339; much better than it was last season at this juncture. April, however, wasn’t kind. In April, Heyward slashed .206/.296/.314. May has been kinder; .278/.371/.367. The only thing missing is power.

First things first, power is weird, especially in small samples. At this point in the season, a handful of swings can alter things a great deal, so keep that in mind.

Heyward’s always been known as a low-ball hitter. The length of his arms has also posed some problems with pitches on the inner half, so he’s usually at his best when he’s taking balls on the outer half and driving them into left-center. For the most part, however, Heyward’s made his living down in the zone.

It may appear that he’s really, really good on balls well out of the zone, but that’s probably due to sample size issues. For example, he doesn’t swing at those pitches often, so good results have a huge effect. Also, a large majority of those pitches must taken for balls, so the majority of pitches in those zones go down as a positive outcome for the batter, which adds up over time.

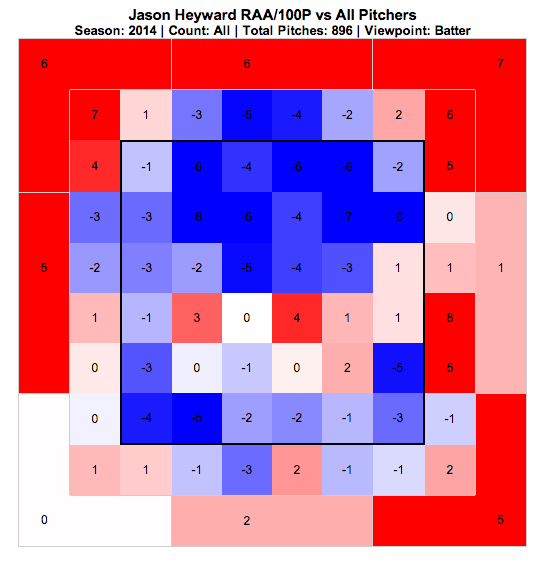

This year has been no different, except for the fact that he’s been really, really bad on balls up in the zone. He hasn’t been great on balls down in the zone either, so positive regression is needed there as well. He’s never had a hole down in the zone, so I’m more confident in his ability to perform better down the stretch on lower pitches.

Part of Heyward’s struggles up in the zone are due to the fact that he’s swinging through more pitches up in the zone than he ever has. Even when he’s made contact on pitches up, it hasn’t been the type of contact he’s looking for.

…

Despite Heyward’s struggles up in the zone, opposing pitchers aren’t pounding those parts of the zone much more than than they did from 2010-2013. Not much of a difference, except for the fact that a few more pitches have been qualified as “up and in.”

The best news regarding the chart above lies in Heyward’s swing%. Going from left to right in the top portion of zone Heyward’s swing percentages are: 39%, 50%, 58%, 59%, 52%, and 34%. From 2010 to 2013, Heyward’s rates were: 45%, 58%, 60%, 62%, 57%, and 41%. Sorry for all of the numbers. In Layman’s terms: Jason Heyward knows balls up in the zone aren’t his forte, and he’s not swinging at them as often.

Heyward’s struggles are a cause for concern, but I believe the power will find it’s way back. His batted ball distance is a little lower – six feet – than it was last season, but his ISO tells you the same story. I was shocked, and a little heartened to learn that his distance hadn’t declined a ton because it feels like he’s popped up a lot. As I said in the beginning power is weird; if three balls didn’t die on the warning track, the numbers would paint a different picture.

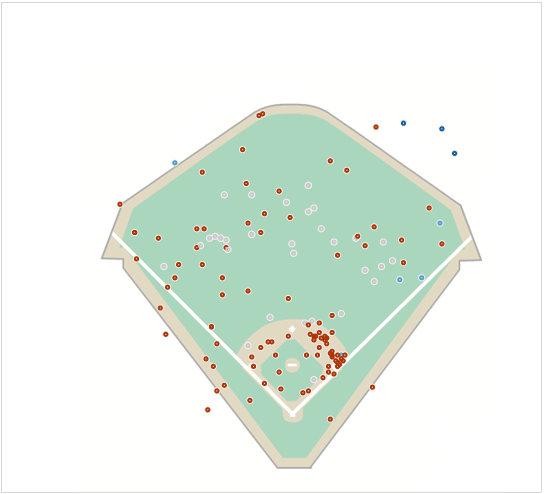

As you can see, Heyward’s had a little bad luck on deep drives. This chart‘s data hasn’t been updated since May 25, so it’s missing the last few games – so it’s missing one home run. He’s had a few balls die not far from pay dirt. Add four extra base hits, and we’re looking at a different player. Alas, the game doesn’t work that way.

In closing, Heyward’s probably let you down this year. Don’t fret, his power ceiling might not be what many of us thought it would be, but he still has a decent shot at finishing with 20 home runs. His walk rate is still good. He’s making even more contact on pitches over the heart of the plate. And he’s healthy. Add in the fact that he’s running more this year and another 20-20 campaign isn’t out of the question. Heyward has shown the ability to tear the cover off the ball for an extended period of time. His swing has a lot of moving parts, so it seems like he’s not 100% right often, but he only needs a few week at full speed to vault himself back into the upper echelon of the outfield.

As always, thanks to Fangraphs for the free data. And thanks to Bill Petti, who puts a lot of hard work into generating spray charts like the one pictured above.