Hall of Fame Index: Who is the least qualified pitcher in the Hall of Fame Part One

As we move to the mound, we have some issues to sort through. The book pretty well addressed the 19thcentury pitchers, so I will address primarily those pitchers selected by the Veterans Committee that we didn’t address in The Hall of Fame Index Part II. That ends up being 20 pitchers. Most of those pitchers came from two primary eras, so dividing them up by era really doesn’t make much sense.

It also didn’t make sense to address all 20 pitchers in the same article. I’ve divided them into three groups. The first group will be those with index scores above 300. If we follow the same benchmark as we did with the position players, we have to say these guys are clear cut Hall of Famers according to any standard. So, our task is to see what markers they have in common to help us identify Hall of Famers in the future.

In order to do that, we are using similar tests as we did with the position players. This time we are adding playoff performance in place of fielding. Otherwise, we will try to define the numbers as we go. Most of these numbers can be found at baseballreference.com. It is a terrific source of information and absolutely free.

Career Value

| BWAR | FWAR | WS/5 | Total | |

| Hal Newhouser | 62.7 | 62.9 | 52.8 | 178.4 |

| Jim Bunning | 59.5 | 66.1 | 51.4 | 177.0 |

| Ed Walsh | 65.8 | 51.3 | 53.0 | 170.1 |

| Amos Rusie | 65.8 | 45.2 | 58.6 | 169.6 |

| Mordecai Brown | 58.4 | 49.8 | 59.2 | 167.4 |

| Vic Willis | 63.6 | 44.0 | 58.6 | 166.2 |

| Rube Waddell | 58.3 | 58.3 | 48.0 | 164.6 |

| Stan Coveleski | 61.4 | 46.2 | 49.0 | 156.6 |

The differences between the three sources are fascinating. They represent a considerable debate in the sabermetric community on how much control pitchers have over their fate. Some think pitchers don’t control much outside of the defensive independent pitching statistics (DIPS). Others think pitchers can control how hard the contact is and therefore can impact the game beyond the DIPS.

The end result is that I’m not comfortable rank ordering pitchers based on the index. The index measures fitness and all of these pitchers are qualified when you compare them with the pitchers selected by the BBWAA. The tight distribution of the scores demonstrates that there isn’t a ton of separation between them anyway. In terms of career value we can see a difference between Newhouser and Bunning and Coveleski, but the rest are within six wins.

The early pitchers normally saw their careers only go a little over ten seasons. So, career and peak value will be similar in most of the pitchers on this list. I could add some commentary on the old school view that pitchers used to be more durable, but I’ll leave that commentary for the book.

Peak Value

| BWAR | FWAR | WS/5 | Total | Index | |

| Newhouser | 58.0 | 58.8 | 46.4 | 163.2 | 341.6 |

| Rusie | 65.8 | 45.2 | 58.6 | 169.6 | 339.2 |

| Walsh | 65.8 | 50.7 | 51.8 | 168.3 | 338.4 |

| Waddell | 56.5 | 56.9 | 46.2 | 159.6 | 324.2 |

| Bunning | 52.8 | 52.9 | 41.2 | 146.9 | 323.9 |

| Brown | 51.9 | 42.2 | 51.6 | 145.7 | 313.1 |

| Coveleski | 59.5 | 43.0 | 46.2 | 148.7 | 305.3 |

| Willis | 54.1 | 35.0 | 48.4 | 137.5 | 303.7 |

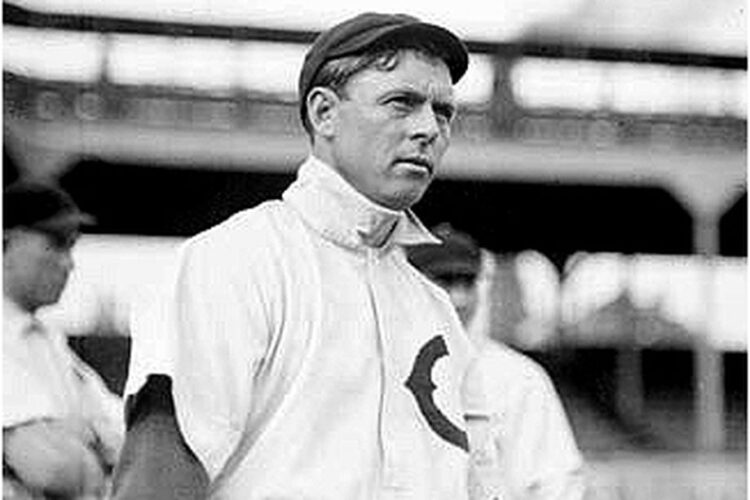

There aren’t two pitchers that illustrate the problems of looking at raw pitching numbers better than Ed Walsh and Mordecai “Three Finger” Brown. In 1906, Brown posted the lowest ERA in history (for a qualifying pitcher) when he went 26-6 with a ridiculous 1.04 ERA. How in the hell did he lose six games? That should probably put to bed the notion that great pitchers “know how to win.” He led the league in shutouts that season with nine.

Walsh has the lowest ERA in history (minimum 2500 innings) with a 1.82 career ERA. So, I guess we can stop the debate over who the greatest pitcher of all-time is. Of course, we know such talk is absurd because it ignores the effects of time and place. This is why we have fancy sabermetric numbers in the first place.

Most fans worry over wins and winning percentage, so we will include those in our pitching numbers. However, we will also include ERA+. It compares a pitcher’s ERA to what an average pitcher would do in that same home environment. We will also include a baseball reference statistic called wins above average percentage (WAApct). It calculates what a pitcher’s winning percentage would be with average run support and fielding support. We will add a column to calculate the difference between that and actual winning percentage.

Pitching Statistics

| Wins | PCT | ERA+ | WaaPct | Diff | |

| Walsh | 195 | .607 | 146 | .586 | +.023 |

| Brown | 239 | .648 | 138 | .577 | +.071 |

| Waddell | 193 | .574 | 135 | .585 | -.011 |

| Newhouser | 207 | .580 | 130 | .575 | +.005 |

| Rusie | 246 | .586 | 129 | .572 | +.014 |

| Coveleski | 215 | .602 | 127 | .581 | +.021 |

| Willis | 249 | .548 | 117 | .569 | -.021 |

| Bunning | 224 | .549 | 115 | .548 | +.001 |

The last column could be called the luck index. As we move down the Veterans Committee list we could surmise that those numbers will be bigger. The total amongst these eight pitchers is .099 or about .011 per pitcher. That’s not a huge sum which means these guys were about as good as we would expect. Of course, breaking down expected records gets difficult because we increasingly add no decisions to the discussion. If you had average run support and average fielding support how would that impact those no decisions? In the modern game we could even somehow calculate average bullpen support. It really throws the question of wins and winning percentage into question.

This is why ERA and ERA+ are still the simplest and most compelling numbers we can use to evaluate pitchers. A pitcher’s job is to keep the other team from scoring and it is still the most elegant and simple statistic we can use to do that. If you are an avid reader of this series I invite you to compare the ERA+ numbers as we move from the legitimate Hall of Famers down to the marginal.

Playoff Statistics

| W-L | INN | ERA | SO/BB | |

| Brown | 5-4 | 57.2 | 2.97 | 35/13 |

| Coveleski | 3-2 | 41.1 | 1.74 | 11/0 |

| Newhouser | 2-1 | 20.2 | 6.53 | 22/5 |

| Walsh | 2-0 | 15.0 | 0.60 | 17/6 |

| Willis | 0-1 | 11.2 | 4.63 | 3/8 |

| Rusie | — | — | — | — |

| Waddell | — | — | — | — |

| Bunning | — | — | — | — |

How do we treat playoff numbers? Well, they are not officially a part of the index, so they first serve as extra evidence. In some cases, we can use them as a tie breaker. Unfortunately, not everyone gets that chance. How do we treat those guys? Furthermore, how do we look at the guys that did have opportunities. Is Newhouser somehow seen as a choke artist because of 20 bad innings?

On second thought, how bad are those innings when he struck out more than a hitter per inning and had a strikeout to walk ratio better than four to one? Also, there is the context of those numbers. Walsh’s White Sox defeated perhaps the greatest regular season team in history and did so with an offense that would be laughable today. Brown had more opportunities on those great Cubs teams, but their results in the World Series were mixed at best.

Coveleski’s numbers are almost as good, but his story is not nearly as famous. He was a brilliant 3-0 in the 1920 World Series, but for whatever reason we don’t remember that one as much. Fame is a fickle thing. That if anything is why we include playoff performance as a category for pitchers, but we don’t dwell on it. Sometimes it helps explains why certain guys got an added boost and sometimes it doesn’t.

BWAR Cy Young Points

| Top 10 | Top 5 | CY | Total | |

| Newhouser | 1 | 3 | 3 | 48 |

| Walsh | 1 | 3 | 3 | 48 |

| Bunning | 3 | 3 | 2 | 44 |

| Willis | 3 | 3 | 2 | 44 |

| Coveleski | 2 | 7 | 0 | 41 |

| Waddell | 0 | 2 | 3 | 40 |

| Rusie | 2 | 4 | 1 | 36 |

| Brown | 2 | 4 | 0 | 24 |

Let’s start with two obvious points. These numbers represent how tight the grouping is in most cases. I would surmise that we will see this across the board with our next two groups as well. The lone holdout is Brown. Why did he score so low when he had such terrific numbers? Unfortunately, there were no Cy Young awards when he pitched, so we don’t know how he was perceived in comparison with other pitchers.

He led the league in wins once and ERA once (not in the same season), so if we go by the modern standard, he might have won one or two Cy Youngs. Still, he pitched on the best team in baseball at the time and perhaps the best team in baseball history. Between 1906 and 1910, the Cubs won 530 games including four pennants and two World Series titles. They had three Hall of Fame infielders that were there primarily for the defense. So, it is safe to say that a part of his value came from having the game’s best defense behind him.